Featured Friend Friday- What’s New with the National Council on Teacher Quality

We are excited to introduce our first Featured Friend of the year – the National Council on Teacher Quality.

With literacy being top-of-mind for many education stakeholders and decision-makers, our team was able to connect with Graham Drake, Director of Teacher Prep Review at the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ), to discuss their new report.

NCTQ’s new Teacher Prep Review on program performance in early reading instruction is particularly timely given recent NAEP scores and a call to action to address reading in America, which was signed by NCTQ, the Collaborative, and nine other education and civil rights organizations.

The new data and analysis – released on January 27th – can be read in full here.

Check out our discussion with NCTQ below!

CSS: Give us a snapshot – what’s going on in the world of teacher preparation regarding early reading instruction?

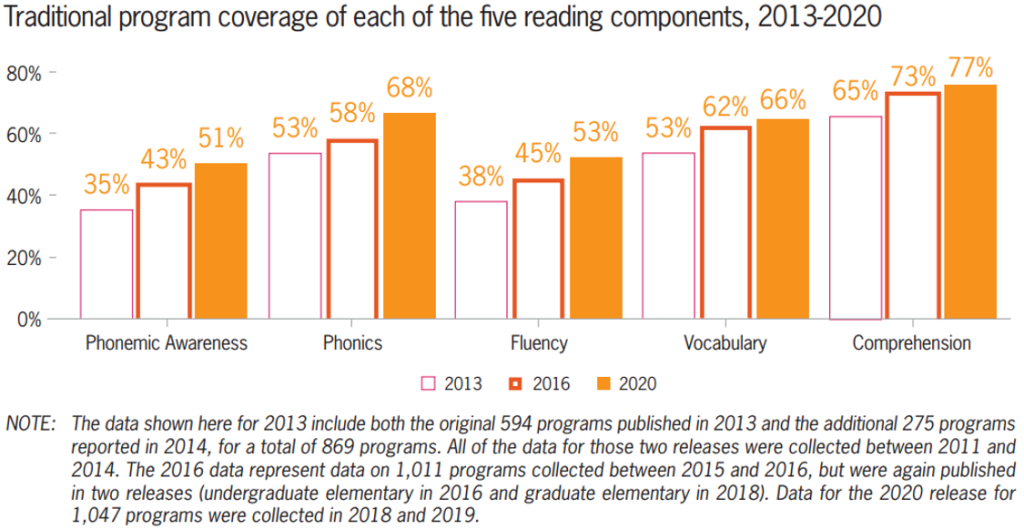

Graham: There are two answers to that question that are equally important. First, the good news – more programs than ever earn an A or a B grade for their coverage of the five components of scientifically-based reading instruction. That’s up from just 35 percent in the first edition of the Teacher Prep Review released in 2013. With 51 percent of programs adhering to reading science, clear progress is being made. While this is encouraging, we can’t ignore that nearly half (507) of traditional elementary programs evaluated are still ignoring the science of reading, even though it has been settled for decades. We can’t help but feel progress is coming too slow when there are over a million kids who enter fourth grade each year not knowing how to read.

CSS: What is the science of reading and why is it important that teacher preparation programs invest in teaching the science of reading?

Graham: Research conducted over 60 years on tens of thousands of children and adults, readers and nonreaders alike, largely under the auspices of the National Institutes of Health, has produced incontrovertible evidence on the most effective way to teach kids to read. Specifically, five critical instructional methods were identified: (1) developing in their students awareness of the sounds made by spoken words (phonemic awareness); (2) systematically mapping those speech sounds onto letters and letter combinations (phonics); (3) giving students extended practice for reading words so that they learn to read without a lot of effort (fluency) — allowing them to devote their mental energy to the meaning of the text; (4) building student vocabulary, a skill closely associated with the final component; (5) developing their students’ understanding of what is being read to them and eventually what they will read themselves (comprehension).

Why does this matter? Literacy skills are fundamental to a productive and fulfilling life. If teachers were genuinely armed with scientifically-based reading methods, we could reduce the current rate of reading failure in the U.S. from 3 in 10 children to fewer than 1 in 10 children.

CSS: What does the data tell us? How are teacher prep programs faring?

Graham: It’s definitely a story of improvement, which is heartening to see. In evaluating programs, we review all reading courses required for elementary teachers, examining each course to determine if each of the five key components of scientifically-based reading instruction are adequately addressed. When we dig in deeper – beyond overall improvement – we can actually see which components are more likely to be covered and which aren’t. Not surprisingly, programs are most likely to omit the most challenging instructional skill teachers need to teach before children can learn to read: phonemic awareness. Narrowly half (51 percent) provide instruction in this skill in which children must accurately identify the speech sounds in words. Unfortunately, this is also the critical first step in learning to read.

CSS: Can you give us a quick “Spark Notes” version of your methodology?

Graham: I can do one better, here’s a 90-second animated video that explains it: https://www.nctq.org/pages/TPREarlyReadingMethodology

CSS: Are there any programs and/or states you can point to as examples?

Graham: Over a quarter of the 1,050 programs we reviewed earned an A by providing adequate coverage of all five components, so there are numerous examples of programs that are getting the basics of reading instruction right. More to the point, there are 15 programs that earn a grade of A+ and serve as exemplars. (You can see a list of those programs, as well as the grades for every program, here.)

There are also a number of states that stand out for having a high percentage of strong-performing programs. Mirroring the latest NAEP reading scores, teacher prep programs in Mississippi performed the highest of any state (repeating that finding from the last edition of the Teacher Prep Review). Utah followed closely behind. Other notable states with strong performances by a majority of their programs are Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Louisiana, New Hampshire, and Oklahoma.

Mississippi provides a strong roadmap for what can be done when policymakers insist upon scientifically-based reading instruction, but it’s important to note the solutions go beyond what’s being taught in teacher preparation programs. Mississippi has also worked to ensure that schools have high-quality screening tools so teachers know where their students are struggling. The state has also gone to great lengths to facilitate practicing teachers’ access to curricula, assessments, and professional development that all reflect the science of reading after entering the classroom. Without this, progress in teacher prep will be squandered.

CSS: Are there any equity implications that your findings present?

Graham: Forty-three million American adults are effectively illiterate, with well over a million public school students on their way to joining those ranks as they reach the fourth grade unable to read. Two-thirds of those children are black and Hispanic, who struggle to achieve in the face of an inequitable education system. The clear fault line for America’s high illiteracy rate is class and race. The ability for students to readily comprehend what they read supports all future learning. Access to reading instruction that is backed by science is should be seen as a right for all children, regardless of their background.

CSS: How might you recommend that education stakeholders best use the findings of your report? How can we all further advocate for quality teachers who are prepared to instruct in the science of reading?

Graham: It’s really important to first note that teachers want to do what’s best for their students. The issue here is a lack of knowledge and support. Too often, even when the five components of scientifically-based reading instruction are taught in teacher prep programs, they are included alongside long-discredited practices. Teachers are unfairly left to decide what works. We need to make certain we are giving them the tools they need to succeed in the classroom.

And we believe that all education stakeholders have a role to play here. We hope these data point to specific ways that policymakers can leverage their influence to ensure more students have the opportunity to learn to read. For instance, we know states are an under-activated lever for bringing programs on board with reading science. In addition to implementing strong licensing tests that specifically measure aspiring teachers’ knowledge of scientifically-based reading instruction, they can also publish first-time pass rates on these tests so programs take ownership for steeping future teachers in this content. They must hold programs accountable for the quality of their reading coursework.

We also urge district policymakers to look at these data for two reasons. One, they can use it as the basis for some frank conversations with their university partners, that the district expects any applicant to have this knowledge. We also hope they look to these data to better understand the critical need for providing practicing teachers in their schools with better instructional materials and PD that reflect the science of reading.

We even encourage aspiring teachers to use these data as the basis for where they train to become a teacher. Most aspiring teachers would be shocked to know that just 50 percent of the programs out there will arm them with the knowledge to teach their students to read, the most important job that an elementary teacher has.

Ultimately, we hope these data are a starting point – not the end. We are pleased to see that the scales are tipping in favor of reading science, and we urge policymakers and advocacy partners to capitalize on this momentum.

About the Collaborative for Student Success

At our core, we believe leaders at all levels have a role to play in ensuring success for K-12 students. From ensuring schools and teachers are equipped with the best materials to spotlighting the innovative and bold ways federal recovery dollars are being used to drive needed changes, the Collaborative for Student Success aims to inform and amplify policies making a difference for students and families.

To recover from the most disruptive event in the history of American public schools, states and districts are leveraging unprecedented resources to make sure classrooms are safe for learning, providing students and teachers with the high-quality instructional materials they deserve, and are rethinking how best to measure learning so supports are targeted where they’re needed most.